6 December 02010

Tony Hall on teaching by not teaching

Tony Hall takes photographs and makes photomovies. At the same time he describes his interests as "thinking about sustainable learning communities, shared learning in public spaces, using social media". Like me, he's a regular at our weekly meetings on self-organised learning, so I've absorbed his views about learning through conversations by osmosis and, indeed, many conversations.

But that doesn't mean that I always agree with him. I've done only a light edit on the transcript of this discussion with Tony — which took place in our regular spot in London's Royal Festival Hall and also involved Patrick Hadfield, Fred Garnett and David Pinto. Hopefully this captures some of the spirit of the conversation, as it circles around rather than progressing linearly, veering as it does so between the serious, the subtle and the throwaway. You may also detect a hint of amused frustration from me (though the most flippant and testy exchange has been edited out, at Tony's request).

As well as conversations, key words in Tony's vocabulary are gentleness and conviviality. Some of my frustration stems from my attempts to square this emphasis with the idea that learning frequently involves elements of challenge and risk. While Tony wriggles away from my attempt at confrontation, it's clear by the end of the discussion that he's no stranger to risk and conflict in his practice. So his way of dealing with my questioning is perhaps an instance of gentleness in action.

I'm not convinced yet, but I am intrigued, and I hope you will be if you cast your eye over the discussion.

Meanwhile, I'm not sure if this will be the last of this series of interviews, at least in this form. The format is obviously text-heavy — which I defend in comparison to audio or video since it's much easier to skim and select from — but the transcription and editing process is not that agile (it's taken me over three months to get from recording this discussion to publishing the blog post). Advice or suggestions for alternative approaches very welcome.

David Jennings: How did you get into teaching, and how did you learn your craft?

Tony Hall: I got into teaching through not wanting to teach, basically. I got into teaching because a few people in a youth centre were interested in something I was interested in: photography. They felt that I could probably help them. "Help" is the wrong word. Not help, just get involved in photography in some way. And being outside of school was important and interesting.

Some of them were unbelievably bright. Some many have been failed by school, but there was a real mix of kids. They weren't much younger than me: I was 21 or 22; they were 16-19. So that environment of being involved with other people, who share an interest, and being able to organise something where everyone begins to learn something together.

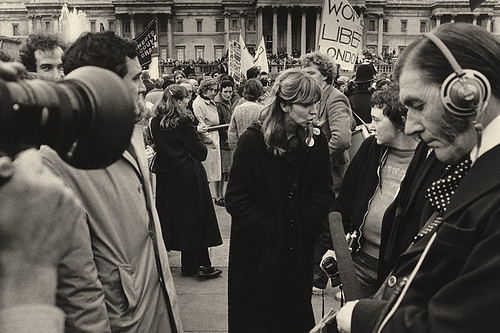

Tony Hall (centre) with the young people participating in photography at his local youth club, London, 1969 (click image for more details)But because I was seen as the so-called photographer, I was seen as the key character in that group. I could get stuff as well: enlargers from up in town; I could get film cheap in Soho, 16mm end rolls that I could get free. That was part of the deal.

David: So you were a fixer, but you were seen as being an expert.

Tony: Yeah, I was the guy who took these wonderful photographs [laughs].

David: Why do you laugh?

Tony: I don't know [both laugh].

David: And when did you realise that was teaching?

Tony: I never ever wanted to realise it was teaching. I never wanted to use the word "teaching" or being a "teacher". I have to use it to work in institutional spaces, but it's not a word that sat comfortably with me.

David: Is there was a word that does?

Tony: No. I think "fixer" is about the best!

David: You stumbled into teaching, and almost as soon as you realised that's what you were doing, you wanted to forget that you were doing it. Does forgetting that you're teaching help you to teach?

Tony: What an amazing question. Yes. It's to do with social relationships. Learning for me is not something you do by yourself — not in the way I do it, anyway. I've always felt I need to learn with other people.

OK, I go away and chew over stuff. But it's what you give other people that gives you a sense of what you may have learnt, just through trying something out, or feeling that you want to do it better.

So learning for me is never ever about being stuck in a classroom and someone telling you how to do something. It's always to do with a process. Various characters get involved in that process. Some are better at explaining things or presenting something, offering up bits of knowledge, or finding something we can use — but it's never just one person who can do all of that. In the photography group, it wasn't just me who could do everything. Kids came along with cameras that they'd borrowed from a grandfather, old things that took film that was 2 1/4" square, which I couldn't get hold of. But someone else found some of this film somewhere. So they fixed it.

It's that make-do, but also making something out of that make-do. It's not learning something for the sake of learning; it's trying to make something. And then the conversations that came out of the practice, whereby you're involved in doing something together, you're trying to make something happen together. You have loads of conversations. Somehow what we were doing in terms of this thing called "photography" wasn't photography. It's more a case of us getting involved with each other and trying something out, having a bit of fun doing it.

It was a year-long process, of making something happen, first of all, making it ourselves, having the space to do that. Out of that came a series of pictures that gave us a sense of our own history. Towards the end of one period when we were being threatened with closure, we made an exhibition around the photographs, to show what we'd been doing to build this darkroom. So somehow that became a way of us saying, "Look, this is our history; this is what's gone on here".

David: So it was a kind of community building?

Tony: I wouldn't even see it that way. In retrospect there's a whole load of theory that can be laid over the stuff that went on.

David: But you're not particularly bothered by the theory?

Tony: I am now, because I'm trying to write a book, and I can't write it without having some sense of reflexive perspective. It's not just one way of talking about the experience. It's not just a narrative with one line; it's a narrative with several layers.

Patrick: It sounds like you're trying to find a shared language to describe what you do.

Tony: I'm trying to find a very specific language to not share with… I feel that institutionalised education isn't a place I want to be. I tried many, many times to be involved inside the space, creating groups and projects inside these organisations. But I found that I spent huge amounts of time dealing with the administrators rather than doing the learning stuff. The first learning project, building the darkroom, was very much being let loose in a space with a bunch of people who had a shared interest. The shared interest was photography, but out of that came a lot of other stuff — lots of conversations, around music and culture. The music scene was very strong then, so there were some very engaged conversations around it, the music we enjoyed and how it related to what we did.

David: So you concentrated on the social, cultural, affective relationships rather than the technical skill of photography. It sounds like you were building resourcefulness, based on finding solutions to achieve particular goals.

Tony: The basic thing was that Kodak idea of "press a button and we do the rest". But I was against that at the same time: it's much more than that. However, with this group of people, as long as we could get a photograph out first of all, and talk about, then something else comes out that. You don't know what's going to come out of it, until somebody comes along and says, "I want to take this kind of photograph". And then you can talk to them in depth.

Patrick Hadfield: How did you get involved in the photography project — out of which you got to be labelled as a teacher — in the first place?

Tony: I was into photography when I was a kid. I left school early, when I was 16, and got a job with a photography place near where I lived, and then I got a job in Soho working as an assistant photographer. I did that for a couple of a years, and then — this was towards the end of the sixties — I got involved with a local youth club, just doing this and that. Out of that came the opportunity to set up a dark room at the club.

What I liked about photography was that anyone could do it, at least in terms of getting started. Sophisticated equipment isn't important: it could be like a two pound camera, as far as I'm concerned…

Patrick: I can't remember where it was, but someone posted a great photograph taken with a camera phone, and a famous photographer said this just proves it's not about the camera, it's about the photograph, it's about what you create with it.

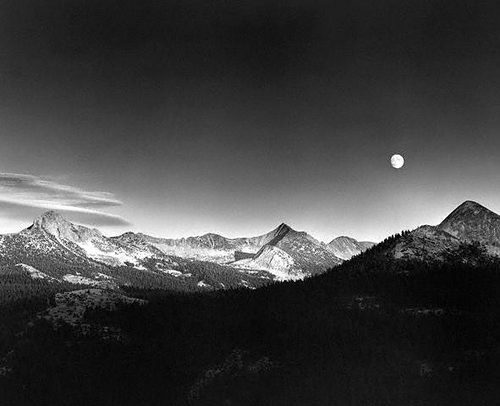

Tony: Yeah, that's right, and just knowing very simple things about light, which takes a little bit of time to think about. So you study someone like Ansel Adams and you get to know what light's about, or what it means with photographs anyway. Then you look around now and you see light, and think about it photographically.

David: Can you say more about that, how… I mean Ansel Adams is a name I've heard, but if I just looked at his pictures, would I…?

Tony: The simplest thing is that you just have to look at where the light's coming from, what time of day you think it is, and what it does for the scene: where the shadows are, and where the highlights are, and how Adams mixes that relationship between what's lit, illuminated by the natural light, and what's not illuminated by the natural light.

So, for instance, he spent a lot of time trying to take a photograph of the moon, and he used to go along a particular road to get from one place to another. He used to take his camera with him to be ready to capture the right moment. Now in those days it was a camera on a tripod, and he had film that just went in the back, so to get a photograph he had to really think, "this is the right time to do it." He had to wait for the light to be in just the right place, from the moon, but also the ambient light. It's not to do with the lights from the city and stuff like that, although there was a town there, it's to do with light at the end of the day that lingers. It illuminates other parts of landscape without dominating. But there were certain things that happen to the features of the landscape that he wanted to get, so he kept going past that scene over and over again, until the scene was illuminated in the right way for him to get the photographs he wanted. He actually tried many times to do it.

Patrick: If you're talking about the photo I'm thinking of — which is the one with the moon over the mountains — in the end he got that image when he wasn't expecting it at all. He just happened to be in the right place at the right time, and he tried to catch it. He wasn't planning to take any pictures that day, he was just taking his daughter somewhere, and they were driving along this road, and he came screeching to a halt — or so the story goes — and saw the image as he wanted it.

Tony: But he tried it many times before, so he knew what he wanted and why. I did a thing later on when I was at college, around doing the same thing with another photographer, called Garry Winogrand. I had a thing about documentary photography, and also liked Lee Friedlander and Robert Frank. I wondered how near you could get to copying what they did, so I did a photograph [below], a copy of a Garry Winogrand photograph, which was a demonstration.

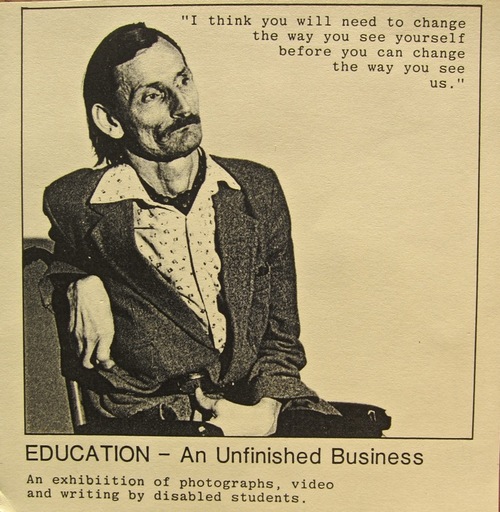

Making a Documentary Photograph: Women's Liberation March, London, 1979, by Tony Hall. Click image for further details of this photograph.We were into semiotics at that time, so we set about breaking that photograph down into what made it, what made it a good photograph. A good photograph is not one element. It's usually about three elements. But if you go to four and five elements, then you really begin to construct something very interesting. Because it signifies in many different ways. There's a cross-relationship between the significant points of the photograph. I spent a little bit of time, a project in my own head, trying to do this photograph by demonstration. The hard thing about documentary photography is that it's supposed to be truths, and I wanted to make it a fiction. So it's about constructing a fictional documentary photograph in one frame, and that was my challenge to myself; that's what I did.

You've talked in the past about how to make teaching gentle, yet a lot of people say that learners need to be challenged — what's the scope for challenging people within a framework of gentleness?

Tony: Throughout the eighties I worked mainly with people in day centres in various places — generally not schools — and a lot of time, I felt as though I was walking into their world, into their environment, and that I had to… I didn't think this through, and I still haven't really worked it out properly, but I always felt that I needed to just be there, as a photographer, and that somehow the conversations would start.

In one environment, for example, there was a dark room, which had initially been for kids in the evening. I set it up as a dark room for people with mental and physical disabilities. This time we got permission from the authorities to do it, so it's the same thing, in a way, as happened in a slightly different way ten years before. I did it with the people there, just trying to use that so it became their dark room, so it became their own space within this institutional space. So they made it in a way: they made it their space with me.

I didn't think of it this way, right? It just happened that way… And it just happened because people allowed themselves to get involved with me in a day centre, and because I was different from what was going on there, because I just hung out there in a way. I always do this: I like hanging out a bit, and seeing what comes out of that. It becomes something we did together, making this dark room… accessible in a way.

There were eleven or twelve people floating around who got involved in this thing. It's always the same: it's one or two people first of all who get interested, and then they know somebody else, who they bring in, who sits on the side of the group, but they then get involved, and once you've got a basic interest amongst those few people, then you can begin to get something out of it.

David: So that was your answer to what it means for teaching to be gentler: you're saying you "be in their space" and just by virtue of being a photographer that acts as a kind of catalyst where something emerges…

Tony: Yeah, I was labelled photographer, so… I could have just sat in there…

David: So I understand that, and I respect that. But I also want to challenge it and say that there are other ways in which people learn: the gentle approach isn't the only effective or "good" one. I was thinking of the example of when Brian Eno was at art school, he was taught by Roy Ascott, and at the beginning of the term all the students did some behavioural profiling. They were then given their profile but required to suppress the traits that show strongest. So, if it said that I'm naturally a quite introverted person, then I have to suppress that introversion for the whole of the rest of the term — or if I'm naturally somebody that tends to interrupt, then I have to not interrupt for the whole of the rest of the term. That approach of actually taking people out of their comfort zone, is that…?

Tony: I'd never ever do anything like that.

David: But people do learn something from that kind of experience. Is that completely antithetical to what you're about?

Tony: Yeah.

David: OK. If you have sense of somebody having some latent capability that you want to draw out…

Tony: I wouldn't want to draw it out.

David: OK, you'd just let it be?

Tony: Yeah. If they want to make something happen, they make something happen.

I was working with people who are special needs. They're in wheelchairs, they've got all sorts of mental problems. The mental problems are sometimes put upon them because they've been stuck in a mental institution, and shouldn't have been stuck in a mental institution. They're in wheelchairs: sometimes they need to be in wheelchairs and other times they don't need to be in wheelchairs. Most of the time they're being patronised by people round them. So, in a way, their identity is constructed through other people telling them how they are in the world.

When you actually begin a series of conversations with them, and continue over a period of time, you… and they know it as well, they know exactly what they want — they just want you to understand them a little bit. And because you're this person who takes photographs, they also want to do this other thing called photography as well. So something like this is going on, round the conversations that are going on with these people. Obviously I go in there with a sort of vaguely framed way of thinking around it, in terms of project I would like to do… [laughing] but sometimes it never works out!

David: I know you read the interview with Fred [Garnett] about re-framing things, about creating your own contexts. When you talked about your experience with the kids in the community centre earlier on, you were creating a context for learning there, almost unconsciously. Whereas Fred's take on how you create a context for learning seems to have as a prerequisite that you actually understand a whole load of things about learning, whereas these people were just stumbling into it, if you like.

Tony: Yeah, that's right.

David: And I'm interested about that, about…

Fred Garnett: The thing I picked up from you, Tony, was that you were saying they saw you as the photographer. That seems to open up other doors, because they're not seeing you as a teacher. By being a photographer rather then a teacher, it lets you do things. I mentioned last week about Mike Wesch and he has this thing about a sense of purpose…it seems to me by you coming in as a photographer, for whichever group it is, you can bring in a purpose, which is about doing photography, without having to go into the learning thing. You just focus on whatever conversations emerge about photography.

So you're sort of a teacher but you're not labelled as that, and I think that gives you a certain degree of freedom, over the context.

Tony: Yeah, that's right.

Patrick: So it's a practical thing. You can sit around in a classroom and intellectualise about taking photographs, but, actually, it's all about going out there, looking at the world and taking photographs — and the skills associated with that. But I'm not sure if to learn about nuclear physics, let's say, you couldn't really have the same approach… [everyone laughing]

Tony: I don't know. There was a guy I knew — this again was back in the seventies — who was interested in computers. He didn't have access to computer, but he got to meet up with some people who were doing a teaching course… and he learnt about computers to the point where he got offered a programming job by Bank of America.

With just his mates, he taught himself in a very very very deep way, to understand this stuff. It was really hard even to get a hold of literature [about computers] then. He pulled together literature from all over the place with his mates and they learnt about computers. He was the one who really made it happen. Something else was going on for him there: everybody learnt from each other, but they learnt in a very very deep way about computers. I didn't have a clue what they were talking about most of the time.

He just got picked up by Bank of America, and he went and lived there, earning huge amounts of money. That sort of thing does happen and can happen. They didn't need teachers, they just needed some sort of sense of "I'm interested in this, I'm really interested in this." And somebody says, "Yeah! Have you tried this?" And they say, "Oh yeah, we've tried that." So it's that real sense of being in a social teaching environment.

David: Can I come back to this question about challenging learners, though? Because I want to understand whether your objection to it is that…

Tony: No, I don't object to it.

David: You don't object to it?

Tony: Nah! If people wanna do that. Fine [laughing].

David: OK, OK, that's fine. Because I wondered if you had sort of ethical objection?

Tony: No, I just think they're nutters really [both laugh].

Fred: But we had quite a long follow-on conversation last week, and Tony and I got into a space where we both feel the same thing, which is that we both teach thinking. We're using different approaches, different subjects, different attitudes. But our view is that what we're trying to do is — correct me if I'm wrong, Tony — to get people that we're working with to think for themselves, and create a process which enables them to make decisions about what they're doing and understand how they're doing it. Would that be fair?

Tony: I though about that a bit more and I was trying to work it out a bit more…

Fred: And you disagree? [Everyone laughs]

Tony: Yeah, a little bit. Because then you begin to look at what thinking is and what learning is. Then you begin to try and unpack learning, and you realise that's not quite it. It is a social thing that's going on, for me it's a social thing. It's us negotiating something to do with an activity that we might do together… For me it's about change as well: changing yourself.

It's not just thinking, it's changing your thinking a bit, because we get constructed in certain ways, through the discourses that prevail in certain institutions, like school…

Fred: You've just come up with a great definition of learning. It's what we did last week, which is we sat down together and agreed. And then we went away, and disagreed.

In a school context, you have to agree and then stay in "agree" mode! [Laughter]

Patrick: I think that formal school education doesn't necessarily want to teach people to think for themselves. When I was at school — and my experience is almost thirty years ago — there was a lot of teaching about orthodoxy… it's kind of formal learning, and it's different from the sort of social learning that you're talking about.

Tony: But you're so put upon in school, I've known quite a few teachers, and a lot of them want to be more open with the kids they're working with. But they can't. That's what pays their mortgage, that's what gives them their life, that's what gives them identity; they can't get out of it.

Fred: The process has now been beset with so many targets that there's less space to move. In a sense you're hanging on to the targets, and, each year, every school and every learner is more successful then they were the year before. Which means you're set ever tighter on the rails, compared with the year before.

Patrick: I think most people would probably agree. I think even Ofsted agree that they've been measuring the wrong things.

David Pinto: In 2008, I quit my job as a teacher. The guy that was running my department was, I think, a very good demonstrator of learning. As the head of department, he was called Lead Learner. Now you might think that's just some language game, but the guy was actually very good. So it seems to me what you were doing is you were demonstrating as a photographer, you were demonstrating that that's what you do, and it's your love of that…

Tony: To tell you the truth, demonstration was not part of my remit.

David Pinto: No, no, at a deeper level than demonstration of photography… You were demonstrating yourself being a learner. All the other kids were doing (because, as you said, they were only a few years younger) was just kind of getting into that vibe, playing within that vibe.

Tony: Yes, that's right.

You were leading, in a way. I mean they were looking at you as a role model, yes?

Tony: Hopefully not…

David Pinto: Do you not think so?

Tony: Hopefully. I'm sure that happens sometimes, but it's up to the other people to decide how they position you, whether as a leader or not, in a way.

Patrick: It sounds to me that you were showing people what was possible, and demonstrating in that way.

Tony: Hmmmm. Sometimes it's just, like, a one-on-one, when someone says, "Ah, I've done a photograph and it hasn't come out right." And I might say, "What's wrong with it?" To which they go, "Der der der duuh"… This conversation goes on, but then what happens later on is that you pick up that they've said something else to their mate, something that relates to something that you said earlier on. That was quite inspiring for me.

Because I didn't really understand that that was what goes on all the time. There's a rippling out, and sometimes people pick up on it. Certain kids in that group became like so-called "lead kids", in a way. They knew it, so my so-called authority as leader, teacher, authority, was transferred across to the kids who really really got into it. One kid especially — he was an academic-type kid, very good at school — he just buried himself in photography and got to know loads of stuff. I always ended up having conversations with him about all sorts of stuff I had little idea about…

David Pinto: But he never contested you.

Tony: No, no, none of that going on…

David Pinto: So that means that your authority was unquestioned?

Tony: It was nothing to do with competition either.

David Pinto: The question I had comes from the experience I had with a whole bunch of kids. It was a forced group, not a self-selected group, so there was a lot of diversity. You do get young alpha males, who, from time to time, want to compete with each other — and also with the teacher, the authority. What you're talking about is self-selected groups. Did you never encounter an alpha male who wanted to…

Tony: Yeah, I worked in IT centres.

David Pinto: OK, how did that go?

Tony: Well… quite often it was mainly boys, so there was a lot of fighting and competition — on different sorts of levels — and in that environment I would just have to try and be myself there.

David Pinto: Did that cause a problem? Did they ever want to be top dog?

Tony: Well, the only way they could compete with me was if I competed with them… so I wouldn't compete.

David Pinto: How did it work out?

Tony: Great. I got to build a whole learning centre on these places — around video, photography, dark room, everything else.

Fred: But IT is kind of a special case though, isn't it? Because if you get alpha males who want to show how much they know, I always used to say, "Fine, you're the specialist then." I'd readily own up that I didn't know that much in that area — particularly in programming. "You can be the monitor for programming then."

David Pinto: Oh, I agree with that, if they want to compete in the topic area. But if they're just wanting it to compete as a social display…

Tony: But that's all right, because it happens every day of your life. Someone's trying to get one over on you one way or another, because it makes them feel better about themselves. It happens in very simple little ways, it's just very much amplified in that sort of environment…

I think it's really hard to try and make anything happen in those environments, really. But because I had longer-term projects that weren't fixed round targets, I had a lot more latitude. In the end it was always about making pictures that related to people talking and writing. It was always about that; it's never just about making pictures.

David Pinto: I was just wondering if in any education system — even the current one — if we avoided that kind of level of competition as a alpha ego, male thing…

Tony: A lot of these centres had a place where you could go and play, and work off that competitive drive — either through playing table tennis or football. So that's good fun, and that way you can beat each other up a bit, you know, without it being seen as me being aggressive to you directly. You can still do something with people without it being too nasty, anyway.

Fred: But that's also so you can take the pressure off by them doing other things that they couldn't act out — those kind of social behaviours that could be disruptive.

Tony: That's right. And it's like you're made to feel as though you're at a party where you're invading their space, and that's not good. But then you just have to be there and, over a period of time, let something happen that leads to them allowing you to be there. So, rather then going there and saying, "Look, this is what you're gonna do today," you go into them and say, "This is what I'm interested in." [laughs]

Fred: Yeah, and ultimately with a group, with mixed characteristics, you have to get to a space where you can negotiate with each of them individually. You can't do that on day one. You can say you're going to do it on day one, but you can't, because it takes time to get to know people.

Tony: That's the great thing about pictures though, because you can negotiate through the picture without being provoked. So you're always displacing the activity and you're talking about this thing here, but you know you're talking with each other, really. You don't have to do eye contact all the time, so the picture becomes a little reflecting device.

When you do talk to them directly, you know that they know and that you know that a little bit of tension has gone. Then you can sometimes just go straight to them and say something, and they can say answer back to you. So that ense of negotiating through photographs is quite important to me as well.

Also putting the camera in front of your head, allowed you to hide [laughing]! So there's a sense of this camera that we can talk about as an object here, and then a photograph there.

The photograph has so much meaning in it, which people want to talk about — somehow this conversations come out of single photographs. Very very interesting.

Fred: A photo is worth a thousand essays. [laughter]

This is one of a series of posts about Agile Learning. Please spare 10-15 minutes to tell us what else you'd like to see on this them via the Agile Learning survey.

|

Follow Agile Learning:

Complete the Agile Learning survey Join the email group (low volume) |

Share |

|

Subscribe to my RSS feed, which covers this blog, my book blog, and further commentary on other web resources (more feeds below)

Notes on Emergent Learning

School it Yourself: Review of The Edupunks' Guide and How to Set Up a Free School

What's holding Open Access publishing back?

On ecosystems, Adam Curtis and positions of power

The Whys and Wherefores of Creativity and Sharing: Review of Making is Connecting

Round-up of recent writing in other places

Purpos/ed: What's the purpose of education

Open, trusting, generous: review of Monkeys With Typewriters, a book on leadership

Do we need an agile learning community of practice?

Unplugged! The Agile Learning newspaper

Can we make a newspaper about self-organised learning?

Tony Hall on teaching by not teaching

Ollie Nørsterud Gardener: an entrepreneur's vision of peer-to-peer learning in organisations

Resilience and scaling down in the face of decline (Dougald Hine discussion, part 2)

Cinema (24)

Cultural Calendar (86)

Curatorial (66)

E-learning (102)

Events (35)

Future of Music (95)

Human-Computer Interaction (62)

Ideas and Essays (37)

Long Now (18)

Miscellany (44)

Music and Multimedia (157)

Playlists (27)

Podcasting (12)

Politics (12)

Radio (48)

Reviews (58)

Social Software (60)

Teaching (23)

Alternatively, see the Date-based Archives

Recommended: RSS feed that combines items on this site, my book blog, and commentary on other web resources

RSS feed for this site only

RSS feed for my book, Net, Blogs and Rock'n'Roll

RSS feed for shared bookmarks

My latest bookmarks (click 'read more' for commentary):

My archived bookmarks (02004-02008)

On most social sites I am either 'davidjennings' or 'djalchemi', for example: Flickr, Last.fm, Ma.gnolia and so on…

Lateral Action — managing creativity

Herd — social cognition

Seb Schmoller's e-learning mailings

Viridian Design Movement

Tom Phillips — artist

Long Now blog — resources for long-term thinking

Longplayer live stream — 1,000-year composition

The contents of this site are licensed under a Creative Commons Licence except where otherwise notified.

Hosted by Paul Makepeace

W3C Standards

Check whether this page is valid XHTML 1.0

Check whether the CSS (style sheet) is valid